At the final count, 51.89% (17,410,742) votes were cast towards an out vote. It was notably cited by the-then Prime Minister in his resignation statement outside 10 Downing Street as a collective national decision away from EU membership:

“the British people have made a very clear decision to take a different path.”

This adjective is quite important in the next section. But for now, its worth pointing out what this political development really reflects. David Cameron, Prime Minister since 2010, first as part of the Coalition and later as a majority, was defeated by a failed gambit. He steered us towards austerity, and against all previewing knowledge, the economy grew and his luck paid off. He again rolled the dice and sailed through the referendum in Scotland, yet again his luck paid off. He did it again for this referendum, and it has failed and we have now neatly divided ourselves squarely in half. Now, he has declared that he will be hanging his compass and hat on the wall to let another ‘captain’ the ship, promptly taking one of the few valuable lifeboats (The Guardian, 24th June, 2016).

This hasn’t been an easy few months. From November when he issued his ‘four pillars’ of reform through to February when he finally confirmed the settlement (The Telegraph, 15th October, 2015, The Guardian, 2nd February 2016) and all the way to the present, including both the referendum and post-result fallout, we have seen the EU dominate the headlines. Something I personally and professionally feel has been missed is the impact on EU citizens living through this spectacle. As two people below state in a video interview shared on Facebook by the ‘Another Europe is Possible’ group, British soul-searching is and has had a demonstrable impact. Regardless of the politics, this is something I don’t think we are thinking about enough:

“To me it does feel a little bit like we are not welcome in this country anymore and people do not like us to contribute as we do” – Jana, from Germany

“The referendum debate is framed around immigration. It makes me feel a little bit awkward. It’s like if you see were sitting next to a group of people that is talking about you. Even insulting and smearing you and you don’t have the right to answer” – Duarte, from Spain

In any case, since David Cameron resigned, all hell has broken loose.The financial markets spasmed, leaders were resigning, and there was a noticeable political vacuum as the triumphant Brexiteers announced their victory in a bunker (see The Telegraph, 24th June 2016). Since the bloody spectacle of the Tory leadership campaign, ending in a de facto coronation of the new Prime Minister, Teresa May, things in government seem to have calmed down, although of course May’s ‘Brexit means Brexit’ mantra alongside recruiting the most Eurosceptic and right wing government for a long time has entailed some of the most confusing contradictions of intent concerning the possible future arrangement with the EU (see Huffington Post, 19th July, 2016). Meanwhile, Labour is often remarked upon as being in ‘meltdown’. The mainstream media and television has obsessed over the clearly orchestrated yet incompetently managed coup against Jeremy Corbyn and the subsequent leadership bid by Owen Smith, who in no sweeter irony had to fight his rival Angela Eagle off in order to present himself as the ‘unity’ candidate (see Thomas Clark’s excellent blog). A fascinating selection of research studies are now amassing using the wonders of content analysis; they are demonstrating how the presentation of this fallout has systemically undermined the Leader of the Opposition. At a time when we needed our politicians and media to keep a cool head and pave a way forward through responsible discussion and reporting, we have seen them all enraptured by the Shakespearian drama of Michael Gove’s knifing of Boris Johnson and allegations of brickthrowing and ‘Trotsky’ infiltration of the Labour ranks, despite Labour now being the biggest political party in the UK and much of Europe. We haven’t even been spared of this by the BBC, who gave TWICE as much time to critics than of allies (see Couldry & Cammaerts, 2016 and Schlosberg, 2016). We have, essentially, been completely bedevilled by our elites, at a time where our democracy could not be more exposed.

‘Brexit means Brexit’, according to our newly annointed Prime Minister

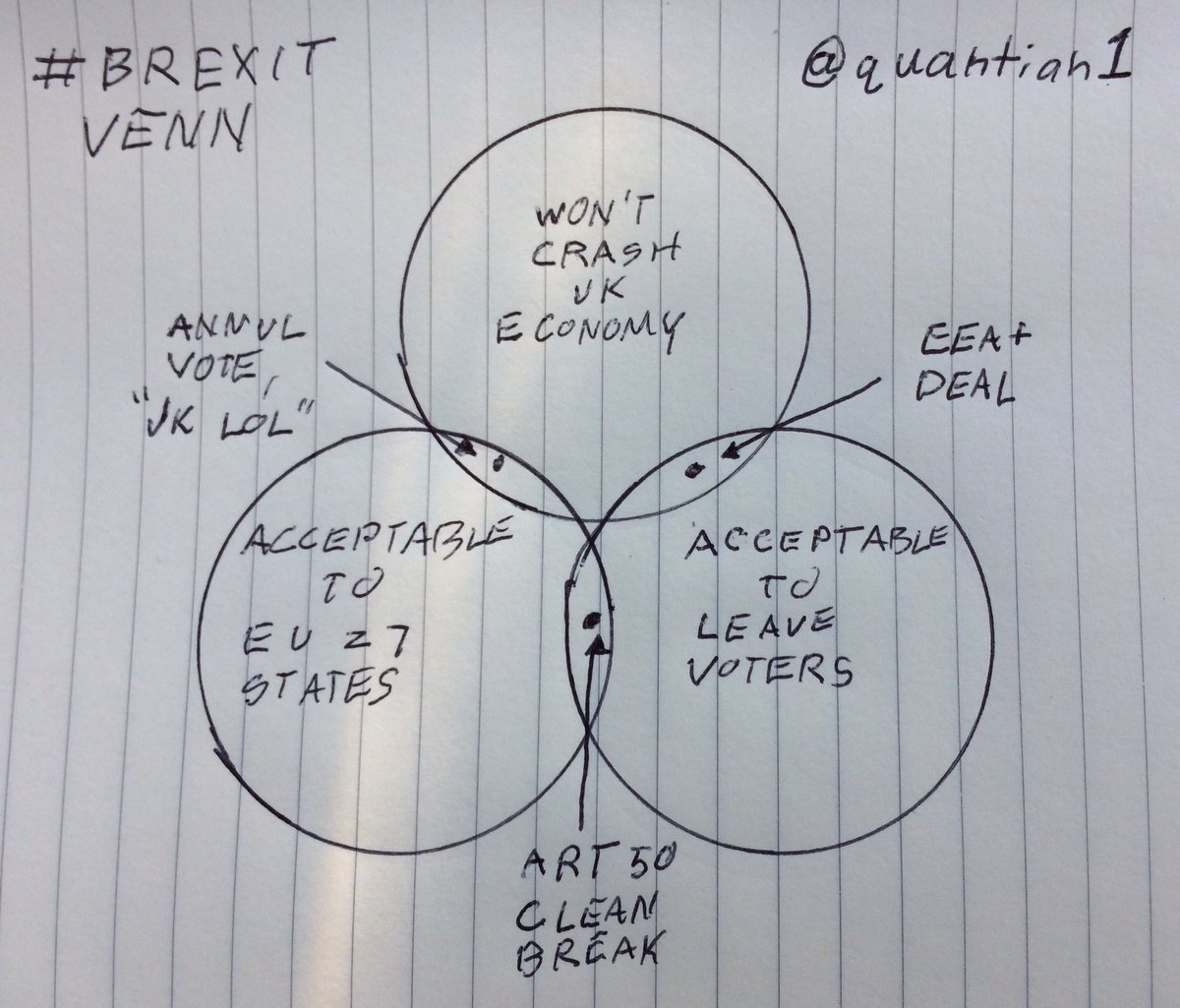

The simplest problem following the Brexit result though is not democratic, but rather, political. Quantian’s diagram below demonstrates this quandary really clearly as being between the economy, the EU, and Leave voters

- an EEA (Norway-style) arrangement (will preserve economic status quo and provide some symbolic independence for Leave voters; but vastly complicated negotiations with the EU)

- Article 50 / World Trade Organisation + trade deals (a clean cut from the EU and promotes the buccaneering ‘Britain rules the waves’ aspiration; but massive economic risk as there are many rules on exit e.g. not being able to sign deals outside of the EU until Article 50 phase is completed)

- annul the vote (the economy will not crash and burn and the EU will remain as it is; of course would cause major anger)

(see also http://www.vox.com/2016/7/5/12098156/brexit-eu-britain-venn-diagram)

(see also http://www.vox.com/2016/7/5/12098156/brexit-eu-britain-venn-diagram)

This is a nuts and bolts context of the post-EU situation as I see it – leaving aside the usual ministerial disputes (The Telegraph, 16th August 2016) or incompetent press releases (Political Scrapbook, 13th August 2016), of course. We have found ourselves on the wrong side of it all – an unexpected result, no post-result planning has been made, the elites were in meltdown, the economy is jittering, a new government has propped up without a single vote being cast for them, and our opposition, both internally and externally, is being paralysed by interests that all oppose the democratic will of the membership themselves

In the name of democracy

My intention of this post was to ask questions, rather than provide a commentary of the politics, however. As you may have already read in a previous post, I voted Remain, out of pragmatism rather than faith or ideology. ‘Reluctant Remain’, I would often qualify it to others. But this disclaimer is not to ‘admit’ my bias, but rather, demonstrate that this whole process is dialogical, and requires asking questions. There has been a disturbing anti-democratic surge as Remainers were shouted down and needed to ‘accept’ the result, that young people had no right to complain because their voting turnout was minor (but see The Guardian, 10th July 2016 as well as the ‘the 75 percent’ tumblr page for young people’s views and experiences).

Of course we should question, even if those questions are awkward or take us into unpopular territory. I did when asking people to consider the moral case for voting throughout one’s life leading to the status quo and then voting to reverse it all. I also did this when asking if it is right to have an electorate voting on such a complex issue despite not deeming it fit to incorporate a formal recognition of political or economic education in our children’s education or offering equivalent further education options for adults. In both cases, these questions are nothing technical, but rather, appeal to the need for a moral compass in guiding our enactment of decisions in the name of democracy.

There is no one answer to these questions, but many: a classic liberal view of citizenship might argue that trying to influence individual decisions is anti-democratic (i.e. that older people should not be discouraged from voting, for example). Conversely, a communitarian view of citizenship might see the basis for ceding one’s own perspective and consider those of everyone around them (encouraging that older person to consider their (grand)children’s views and placement, for example). Similarly, these same perspectives might see political and economic education as being a personal responsibility or as a social good requiring collective action. My point though is that democracy is not just about ‘majority’ votes or even voting at all: it is about compromise, respect for difference, and ensuring that the society as a whole is enriched enough to make a decision that is considered, and the moral and civic reasoning above is the sort of thing I argue is necessary for mapping a political debate landscape, and save it from falling into technical claims (which of course, it did as the £3600 per families Remain figure, and the £350 million-a-week for the NHS Leave figure, both did).

In any case, since we already have the vote outcome, those questions are clearly academic. But what is not, however, is the subsequent moral democratic questions that have emerged from the vote. We know that in Article 50, there is provision to leave the EU according to the country’s own ‘constitutional requirements’. The UK has an unwritten constitution, which means that the way forward is unclear. There is an ongoing court battle as to whether it is ‘royal prerogative’ (exercised through the Prime Minister) or parliamentary action vis-a-vis abolishing (e.g. the European Communities Act) or enacting new legislation (an ‘an EU withdrawal’ Act) (see The Independent, 11th July 2016). According to Adam Tucker (a Senior Lecturer at Liverpool Law School), beyond democratic principles per se there is provision to do it through Parliament.

The problem, in either scenario, though is this: the majority of MPs in Parliament are Remainers. If the enactment of EU withdrawal was through the Prime Minister, is the use of an archaic executive mechanism to enact a majority public decision ‘democratic’? Conversely, how can a parliamentary democracy, having had a debate about membership of a body that is alleged to overrule said parliament, decide through a referendum (that is advisory) that the parliament MUST enact? If parliament is/should be sovereign, surely it is the final arbiter? Because the referendum was consultative, not legislative (like the 2011 AV referendum was), what constitutional basis is there for parliament to be forced to go with the Leave vote?

Similarly, how can a vote be upheld as democratic when the vast majority of the actors on both sides lied through their teeth, where truth was mentioned as an insult? How can 52% be a ‘clear’ majority when Denmark, Ireland, Italy, Sweden and Switzerland all have provisions to establish an actual percentage as a minimum benchmark? Further, if 48% of the population is being overruled, how can democratic civil society thrive as the UK pursues a generational shift in its political and economic trajectory?

I am not advocating the annulment option. I am, however, arguing that more democracy needs to be injected. Once a constitutional path is forged, there needs to be another referendum on the deal. We cannot undergo such change without a say on the new settlement – whether that means massive industrial and trade changes, further constitutional crises in Scotland and Northern Ireland, or potentially controversial continuations of some pre-existing policies (e.g. free movement).

We also need to learn the lesson of minimum turnouts, minimum thresholds for changes to the status quo policy, as well as stronger legislation on libel etc. to regulate public debate. What we saw during the referendum was a shameful indictment on our democracy, seeing so many callous threats being issued (e.g. concerning Turkey, terrorism, economic meltdown…I could go on).

Of course, ‘democracy’ is basically a synonym for compromise and fudging outcomes. Its crap but it works better than alternatives. However it only works when there are systems in place to protect its enactment. Protesting rights, free speech, transparent institutions, good governance, clear rules on referendums and so on. No one can call the Brexit decision ‘clear’ – that was simply David Cameron’s ‘get out clause’ to justify his immediate resignation.

Witnessing a newly coronated PM with a decisively contrasting agenda to her predecessor without a General Election, with the likes of Boris Johnson as Foreign Secretary, is a boot in the face to the ‘sovereignty’ and ‘democracy’ arguments being asserted during the referendum campaign.

To enact Brexit, requires decorum and due process, within a clear environment that supports the principle of equal and fair participation in society. Our ability to honour and enact the principles our society is supposed to support, which we have fought countless wars to promote and uphold, is key. One thing is for sure: we need to refind our moral compass if we are to iron out for future democratic exercises the relationship between the citizenry, parliament, our electoral rules and our political claims.